Export Growth

October 23, 2025

International Monetary Fund sees risks in global growth prospects

Written by Greg Wittbecker

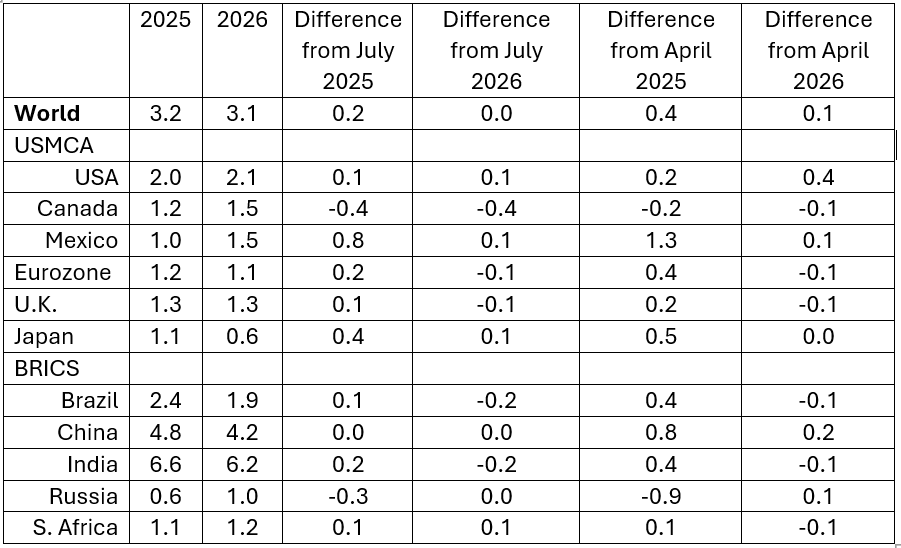

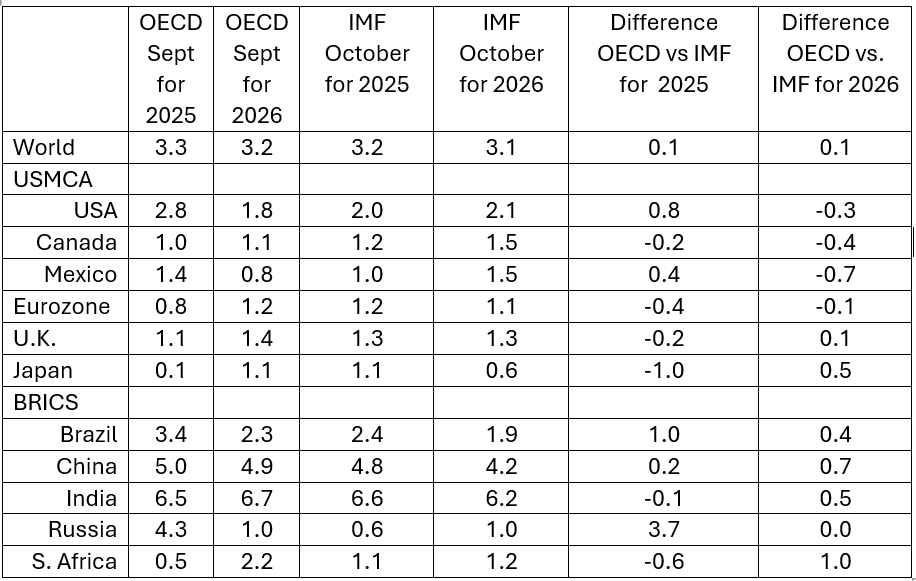

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has issued its October edition of its World Economic Outlook. This forecast is useful not only to compare changes in the IMF perspective, but how the IMF looks at things relative to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Interim Report for September.

IMF’s projections for global output

The IMF cited the following concerns in its forecast:

- Like the OECD, they saw a great deal of front-end loading of production and global trade to beat expected tariff increases in the second half of the year. That “borrowing of demand” is likely to mean slow growth in the second half.

- Labor shortage due to restrictive immigration policies may hamper growth in G7 countries.

- Loss of foreign aid from the U.S. could stunt emerging markets.

- The effects of tariffs e.g., pass-through-to-consumer prices will become more pronounced in the U.S. with some blowback on exporting countries to the U.S.

Overall, the IMF changes from its July forecast are not earthshattering from a global perspective. World growth is unchanged; the U.S. and China are staying the course, with the Eurozone a touch longer.

Closer to home, our USMCA partners saw substantial change.

Canada saw a big markdown in prospects. This is clearly a reflection of the hardline the Trump administration is taking with Canada on its broad exports, of which 80% go to the U.S. and now carry a 35% tariff if they are non-USMCA compliant. Canadian aluminum exports now carry the 50% Section 232 duty, and aluminum exports represent about $13 billion/year in export earnings.

Mexico got a large upgrade of 0.8% despite facing a potential 25% tariff from the U.S. on non-USMCA compliant exports. This caveat about USMCA compliance is important to Mexico because of the massive U.S. investment in IMMEX/maquiladora manufacturing sector. U.S. companies have created huge dependencies on Mexico manufacturing of vehicles, medical devices, white goods, electronics, the list goes on.

When the IMMEX program was set up, the assumption was that most of the raw materials would be coming from the U.S. They would be transformed into finished products and exported back to the U.S. This was the premise behind why Mexico created tax preferences for the companies.

Today, between 40%-54% of raw materials, parts, and components still originate from the U.S. The rest are likely coming from Asia. The Trump administration wants this loophole closed, as it means Chinese products are entering the U.S. under the cover of USMCA exemption.

This priority is why we believe the U.S. cut a deal with Mexico before it cut a deal with Canada. The U.S. investment is much larger in Mexico and growing trade with Mexico is another indirect way for the U.S. to punish China.

Another interesting change is Japan. This again seems to be linked to trade negotiation with the U.S. and the expectation that a deal gets done. It also has important geopolitical ramifications as Trump wants a strong Japan to counter China’s influence in the Pacific.

The IMF versus the OECD

By and large, the OECD is more optimistic than the IMF. We doubt this has anything to do with the timing of their report being a month earlier. Not that much bearish news came out in the interim between the two reports.

The OECD appears to have assigned a lot more value to the first half 2025 front-end loading of trade and growth in the U.S. However, they also are more pessimistic on 2026 because of the “borrowing of demand” and the impact of the tariffs on U.S. consumers.

Being Paris-based, the OECD is front and center within the Eurozone and that seems to have made them much more bearish on European prospects.

Russia fares much better in the OECD’s view. This outlook seems shaky to us as the Trump administration rachets up pressure on countries buying Russian oil.

South Africa, Africa’s largest economy comes off poorly, according to the OECD. They have systemic problems with energy supply, and their commodity-dependent economy could be vulnerable if demand for their industrial minerals weakens in the second half.

It is worth nothing both the IMF and OECD are quite bullish on China and India.

Why this matters

Both organizations are highly respected sources of economic forecasting. The IMF forecasts might warrant more weight because they are an active lender to many low- and middle-income countries. This means they are on the ground seeing localized economic activity in the emerging markets.

From an aluminum perspective, if we see GDP growth in the 1%-2% range amongst the G7 countries, it should deliver aluminum demand growth of between 1.5%-3%. Historically, the mature G7 economies can gain at 1.25 to 1.5 times their GDP growth rate.

Emerging markets like China and India have thrown off aluminum growth rates greater than 2 times GDP in the past. We believe those days are gone as these economies are now of a critical mass and it is hard to drive that much growth in the absence of big infrastructure projects. Now, it becomes a matter of getting their emerging middle classes to spend more. Nevertheless, with GDP growth of 5%-6.5%, it’s not unreasonable to see domestic aluminum demand growth coefficients that mirror G7 growth, meaning 6%-8%