Carbon Neutral Initiatives

September 18, 2025

Canada’s $5bn relief fund with aluminum focus rekindles debate over subsidies

Written by Nicholas Bell

The Canadian government has rolled out a sweeping set of measures to shield industries most exposed to U.S. tariffs, with aluminum singled out as critical to the country’s economic future.

On Sept. 8, Industry Minister Mélanie Joly announced a $5 billion Strategic Response Fund (SRF) as part of a broader package designed to offset tariff impacts, provide liquidity, and reorient procurement policies toward domestic suppliers.

Ottawa is positioning the fund to help smelters, recyclers, and fabricators, promising flexibility to finance pre-development work and front-end engineering studies.

Managed by Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, the program allows for non-repayable contributions up to $1 millions will be available through an expanded Regional Tariff Response Initiative, now funded at $1 billion over three years. The business Development Bank of Canada’s loan ceiling for small and medium-size enterprises (SME) rises to $5 million, while the Larger Enterprise Tariff Loan Facility gains more flexible terms.

Under the Strategic Innovation Fund (SIF), organizations proposing a large-scale project costing greater than $20 million could receive disbursements from the government starting at $10 million, which is being carried over into the SRF policy with a wider applicability.

The measures come alongside a “Buy Canadian” policy initiated in June that will mandate federal agencies, Crown corporations, and eventually provinces and municipalities to prioritize Canadian suppliers and local content.

From innovation to strategic response

The SRF replaces the Strategic Innovation Fund (SIF) but carries forward its innovation support role, while explicitly addressing the market disruptions caused by U.S. trade policies.

Here are some past SIF disbursements:

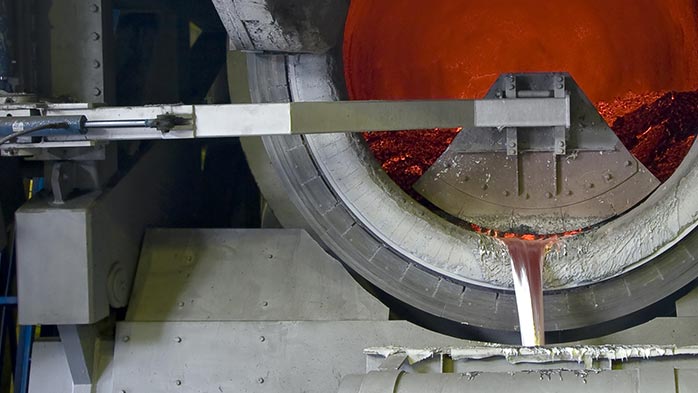

- Aluminerie Aloutte received $15 million toward a $474.7 million project to implement AP40 tank technology in 2019.

- Alcoa’s Deschambault smelter secured $10 million for a $85.2 million project to increase production capacity by expanding potline amperage in 2019.

- Elysis (Alcoa/Rio Tinto joint venture) received $60 million toward a $558.3 million project developing zero-carbon smelting technology in 2018.

Tariffs and counter-tariffs

The initiative comes after months of tit-for-tat protectionist measures between Canada and the U.S.

The U.S. imposed 25% tariffs on Canadian aluminum on March 13, sparking $29.8 billion in reciprocal Canadian tariffs, including $3 billion on U.S. aluminum products.

Ottawa added auto-sector tariffs in April and imposed $30 billion in additional duties on U.S. goods after Washington targeted Canadian exports.

By Sept. 1, Ottawa rolled back some consumer-goods tariffs but kept duties on U.S. aluminum and automotive exports.

Canada ran surpluses in primary and semi-fabricate aluminum in 2024, prior to heightened protectionist measures, exporting nearly 2.74 million metric tons (t) of unwrought aluminum to the U.S., compared with just 82,328t flowing in the opposite direction.

Canada also ran surpluses in forms like bars, profiles, and wire. U.S. producers maintained surpluses in a few product forms as well: aluminum plate/sheet/strip (274,000t exported to Canada versus 126,483t imported), motor vehicles for the transport of goods (321,553 units exported from the U.S. to Canada exports of 168,435 units), among others on a smaller level.

Industry group criticizes Canadian support

The American Primary Aluminum Association (APAA) denounced Canada’s SRF as a fresh round of subsidies that distort global trade, layered on top of what a 2019 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) policy paper estimated at $851 million annually in Canadian government support for aluminum between 2013 and 2017.

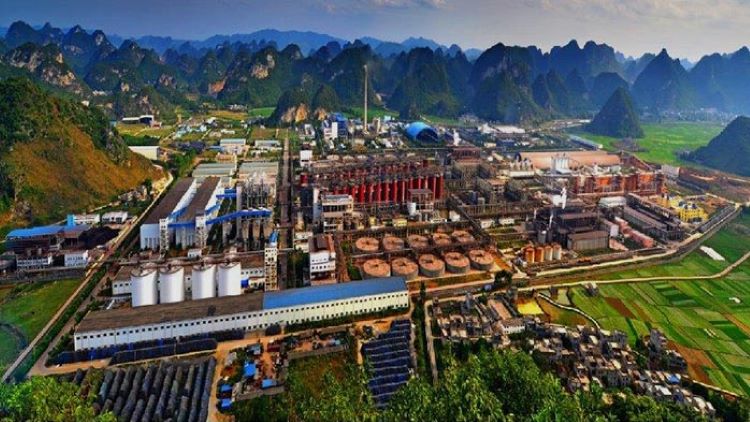

APAA President Mark Duffy tied government support directly to the preservation of Canada’s 10 smelters, contrasting it with the U.S. industry’s decline to just four smelters.

“Rather than allowing their producers to compete on a free market basis, Canada has chosen to double down,” Duffy said, while praising Washington for maintaining a 50% tariff line on Canadian aluminum.

From APAA’s perspective, government aid allows Canadian smelters to shrug off tariffs and keep shipping into the U.S., worsening the conditions for U.S. operators.

The APAA’s membership helps explain its stance. The group is comprised of Century Aluminum and Magnitude 7 Metals. The latter has idled its U.S. smelting operations, leaving Century as the only active member operating smelters.

Notably absent is Alcoa, the other producer still running smelters domestically.

Pittsburgh-based Alcoa also operates multiple smelters in Québec and has received Canadian government support, which leaves the company with little incentive to publicly criticize the SRF. In contrast, Chicago-based Century Aluminum has not reported a direct tariff-related hit to its results, while Alcoa has estimated U.S. tariffs have cost it more than $100 million.

The dynamic underscores APAA’s positions largely reflect Century’s interests, whereas Alcoa, though still a major U.S. producer, has cross-border exposure.

OECD study breakdown

The OECD’s 2019 study, “Measuring distortions in international markets: The aluminum value chain,” is the key evidence APAA cites.

It found that Canadian aluminum producers, like Rio Tinto and Alcoa accounted for $851 million in quantified support, mostly in the form of subsidized energy.

Alcoa accounted for just under 80% of that total, while the remainder was mostly afforded Rio Tinto.

Québec’s power pricing is central.

Decrees from state-owned hydroelectric power provider Hydro-Québec allow some smelters to purchase electricity at rates well below other large industrial users. For an aluminum smelter consuming terawatt-hours of power annually, that represents substantial sums in effective “non-financial government support” the OECD classifies as subsidies, regardless of whether they’re framed as economic development policy.

To be sure, Rio Tinto and Alcoa also received 30-year, zero-interest loans from Investissement Québec in the 2000s, conditioned on maintaining or expanding operations. When investments fell short, repayment schedules were renegotiated, further underlining how the risk was borne by the state.

Parallel U.S. policies

APAA frames Canada’s subsidies as unique, but the OECD report and other evidence show non-market support is not confined to Canada. Smelters in the U.S. have also benefitted from state and federal interventions.

The same OECD study delineates government financial support into a couple of distinct categories: direct transfer of funds, tax revenue concessions, government revenue concessions, transfer of risk, and “induced” transfer concessions by government-mandated regulations and the like.

Alcoa’s Massena smelter in New York receives discounted hydroelectricity allocations from the New York Power Authority, a form of state-level subsidy parallel to Hydro-Québec.

Century Aluminum’s Mt. Holly smelter in South Carolina has had multiple power deals with Santee Cooper, a state-owned utility, which effectively subsidized operation by providing power below full market rates.

On the federal side, U.S. aluminum producers have tapped tax incentives and direct funds.

The 45X manufacturing tax credit, now slated to be phased-out within the decade following the passage of the “One Big, Beautiful Bill Act”, has been used by Century and Alcoa to reduce tax bills. This was a support mechanism that would otherwise have left profits in negative territory during certain quarters.

In 2024, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) awarded Century Aluminum $500 million in support of a new smelter project, with the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations provided $10 million to jumpstart the Phase 1 planning.

The award announcement came alongside a commitment of another $150+ million in funding spread across new casting technology at Constellium’s Ravenswood mill, upgrades for Golden Aluminum’s mill in Colorado, and the construction of a salt slag recycling facility operated by Real Alloy.

While the forms of support differ (or don’t, in some cases), both industries operate within policy environments that are completely market-driven. The full scope likely extends beyond the most visible federal and state programs to include numerous county, city, and local measures as well.

Subsidy or industrial policy?

Taken together, the evidence suggests that both Canada and the U.S. provide meaningful if differently structured, supports to their aluminum industries.

Canada’s focus has historically been on low-cost energy and project-based federal and provincial funds, while U.S. support has manifested through tax credits, state-level power allocations, and federal disbursements tied to capacity innovation and preservation.

The APAA’s argument resonates when focusing narrowly on Québec’s hydropower arrangement or the scale of the SRF. These are clear and quantifiable subsidies. But the U.S. aluminum sector is not a purely free-market industry either-it has repeatedly been sustained by government intervention.

The debate ultimately hinges less on whether subsidies exist than on whether such policies are legitimate industry strategy or distortions requiring countervailing action.

In that sense, the APAA’s campaign reflects a broader ideological clash.

Should the North American aluminum market be governed by truly free-market principles or by interventionist policies aimed at preserving strategic industries?