Building & Construction

October 13, 2025

Plugging the leaks, Part 1: How aluminum trade groups are closing gaps in Section 232

Written by Nicholas Bell

The latest round of Section 232 inclusions captures a growing number of “other” or residual product categories.

In cases where a sector’s dominant tariff classification covered too few specific product codes, or where exporters began reclassifying goods under alternate Harmonized Tarriff Schedule (HTS) codes to avoid the 50% ad valorem duty, U.S. import data began to show rising volumes in those reclassified codes.

Many of these were subsequently nominated for inclusion under Section 232, turning the process into a policy game of whack-a-mole.

A new petition window opened between Sept. 15-29 for organizations seeking to add aluminum-bearing goods to the Section 232 derivative list. This followed the Aug. 15 implementation of roughly 200 additional HTS codes, which itself came just a little while after the June 5 addition of more than 150 aluminum derivative categories.

Aluminum Extruders Council (AEC)

The AEC argued that rising imports of aluminum derivatives have “eroded business opportunities for domestic producers supplying or competing with these industries, thereby undermining the Section 232 program.”

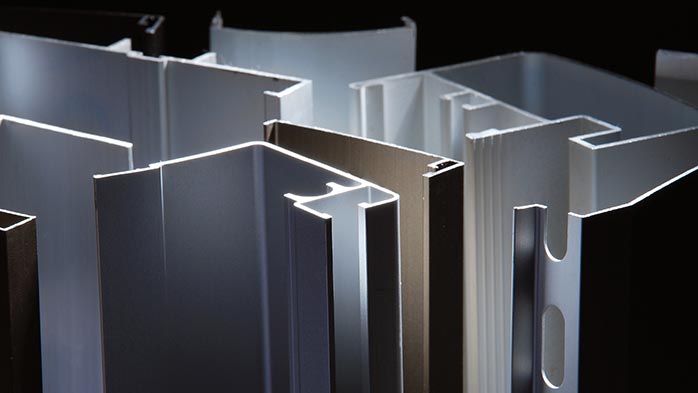

Products cited in the AEC’s filing included extruded aluminum clamps, solar-panel racking rails, tent poles and frames, and Bimini tops, all representing downstream outlets for U.S. extrusion demand.

The Council submitted petitions covering nearly 70 HTS codes, adopting a “shotgun” approach, or a broad submission strategy to distribute proposals across several product categories, similar to that used by the Can Manufacturers Institute (CMI) in the same submission window discussed later in this analysis.

The proposed codes span a wide range of headings. For example, base-metal signage plates (HTS 3810) align with domestic production by firms such as Vulcan Inc., one of the few U.S. rolling mills specializing in signage stock.

Some of the AEC’s proposed HTS codes have a clearer relationship to aluminum than others. The Council’s filing does not break down all 70 individual codes, but those it explains in detail typically involve product with evident aluminum components or applications.

In other cases, like textile articles (HTS 6306.12.00), travel goods (HTS 4202), the aluminum content may vary considerably across products, reflecting categories in which metal frames, poles, or fittings are used sometimes but not uniformly.

By contrast, headings such as plastic builder’s ware and kitchenware, under the 3925 HTS category, appear less directly tied to aluminum and more indicative of an effort to limit import substitution by non-aluminum materials rather than to address demonstrable injury from aluminum-bearing imports. Put another way, their inclusion may be intended to discourage substitution toward lower-cost plastic alternatives by extending tariff coverage to materials that compete with aluminum. These particular codes are an example of some of those not explicitly outlined in the AEC’s filing.

Bicycles

Some overlap exists between AEC petitions and those filed by other trade bodies or companies, including bicycle and component manufacturers such as Guardian Bikes, which recently financed construction of a large-scale frame production facility in Seymour, Indiana.

The company has estimated production of approximately 500,000 bikes in 2025, though this remains a fraction total U.S. consumption estimates of 10 million units annually.

In Guardian’s petition, the company estimated that reshoring 100% of U.S. bicycle imports would equate to roughly 40 million pounds of annual aluminum demand, but it did not specify which import baseline that assumption was derived from.

One of the filing’s section cites average imports of about 15 million units annually between 2017 and 2023, based on U.S. Commerce data, while 2024 Commerce data peg total imports at 11,039,119 units, and the company itself describes the current market as “more than 10 million units annually.

Using those three figures as reference points, Guardian’s 40-million-pound reshoring estimate implies a range of roughly 2.7-4.0 pounds of aluminum per bicycle, depending on which baseline is applied.

Taking those figures and applying it to the company’s projected 500,000-unit output would translate to roughly 605 to 907 metric tons of annual aluminum consumption once production reaches that scale. Based on Commerce’s 2024 import data, the more precise midpoint would suggest closer to 820 metric tons of aluminum demand for that output level.

North American Die Casting Association (NADCA)

The NADCA has petitioned for the inclusion of nine additional HTS codes, following about a dozen submitted in the prior round.

Based on 2024 import estimates, the association calculates that these imports displace 105,000-121,000 metric tons of domestically produced high-pressure die-cast aluminum annually.

Targeted product forms include air and vacuum pumps, compressors and fans; small- to mid-size motorcycles (ex. Scooters); all-terrain vehicles (ATVs); lamp and lighting fixtures; metal-framed furniture; and aluminum battery housings.

Separate from the NADCA’s filing, several other petitioners targeted the “other articles of aluminum” subheading under Chapter 76 – an already complex portion of the tariff schedule.

Within this section (HTS 7616.99), products are further subdivided through a cascading series of “other” classifications that create multiple layers of residual categories. The statistical suffixes include castings (7616.99.5160), forgings (7616.99.5170), articles of wire (7616.99.5175), and yet another residual “other” (7616.99.5190) – each nested within a broader “other articles” grouping.

These petitions, submitted by several independent casting and forging companies rather than by the die-casting trade association itself, sought to add a range of aluminum castings, forgings, and fabricated components to the derivative list.

The filings illustrate how easily products can be repositioned within the HTS framework, as each successive “other” category offers an administrative avenue through which imports can avoid more clearly defined tariff classifications.

The convergence of separate petitioners on nuanced codes within the HTS 7616.99 section line items shows how sub-sectors are converging on similar arguments about circumvention, even when the line items differ.

Molds

Several precision tool and die manufacturers have requested that molds for metal, carbide, mineral materials, rubber, or plastics be added to the Section 232 derivative list. Although most petitions center on molds tied to steel derivatives, the implications for the aluminum sector could be substantial.

While these molds are not made from aluminum, they include products like die-cast dies integral to the production of aluminum parts.

Specific petitions refence both injection molds and die-cast molds within the broader HTS 8480 category, though it should be noted that this category does not include ingot molds, which are classified under a separate HTS chapter.

Many U.S. die-casters import molds and dies from overseas but use them domestically in the manufacture of aluminum components.

Expanding inclusion across the broader HTS 8480 category would cover a far wider range of molds used in aluminum and other metal-forming operations.

Because the U.S. overwhelmingly imports these molds from China, which already faces a dense web of tariffs under Section 301, reciprocal retaliatory measures, “fentanyl-related” tariffs, and possibly forthcoming tariffs, the practical impact of adding them under Section 232 could be limited.

However, the legality of some of these tariff regimes is currently under review by the U.S. Supreme Court, and if portions of those measures are struck down, new Section 232 inclusions could function as a backstop to maintain trade restrictions.

In that sense, expanding derivative coverage to molds may carry less immediate trade impact than strategic significance.

These industrial petitions reveal how derivative coverage is being used to close the remaining gaps in the aluminum supply chain. Part 2 examines how the same logic is being extended to finished goods, from wheels and vehicles to cable, powders, and even canned food and beverage products.