Global Trade

June 16, 2025

Why China's aluminum capex stays so low

Written by Greg Wittbecker

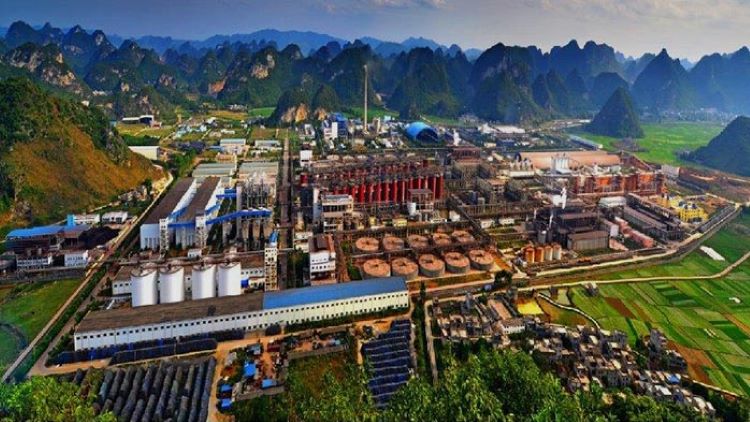

We recently took note of the Tianshan Aluminum brownfield expansion in Xinjiang, China. Tianshan is a huge primary smelter built in 2010 as part of Beijing’s plan to boost economic growth in this autonomous region of far western China.

Tianshan has announced a 200,000 metric ton per year (mt/y) “creep” project that will take them to 1.4 million mt/y. The capital cost will be 2.23 billion renminbi (RMB), or about USD $311.1 million. That translates to a capital cost of about $1,556/mt. By Chinese standards, that’s on the high end, but it’s still well below the best examples outside China, which have come in between $3,500 and $4,000/mt of installed capacity.

I spent parts of two years in China with Alcoa, charged with understanding how the Chinese were able to consistently build their smelters so cheaply. Some things were readily apparent; others took time to surface.

Broad state subsidies

The OECD has published extensively on the degree of Chinese state subsidies to aluminum over the past two decades. You can check their work out independently. The key points: subsidies were pervasive and concentrated among the largest aluminum companies. Attractive financing was one major element. Infrastructure development was another. Beijing also provided export rebates for fabricated aluminum from 1985 to 2024, helping to stimulate demand for primary aluminum.

Size matters

One of the obvious things that stands out is scale. Tianshan’s existing capacity is twice the size of the proposed EGA smelter in Oklahoma, and that’s 15 years old. Most of the smelters in Xinjiang exceed 1 million tons of capacity. When you build that big, you spread infrastructure costs over more tons.

Standardized design, scaled up

Chinese smelters are built to standard, modular designs. Customization is minimal. You walk through one, and you’ve basically walked through them all. That’s very different from the West, where plants tend to be purpose-built.

Time is money

Some Chinese smelters have been built in as little as 12 months. Once a project is approved, it moves fast. Provincial governments want economic growth and offer low-cost land with few regulatory delays. As long as projects meet national production limits, Beijing stays out of the way.

Contractors are held accountable. Construction contracts do not allow for time or cost overruns. If they miss deadlines or budgets, the liability is theirs. Contingencies are rare.

Overcapacity in supporting industries

One Belt One Road (OBOR) is often framed as China’s grand global development push, but it also serves a domestic purpose: exporting China’s massive overcapacity in industrial sectors like steel, concrete, and electrical components. That overcapacity also benefits domestic projects. Smelters like Tianshan get access to low-cost materials and equipment from a hyper-competitive, oversupplied supplier base.

Cluster benefits and regional specialization

In regions like Xinjiang, Yunnan, and Inner Mongolia, a critical mass of aluminum projects has created dense networks of suppliers, contractors, and repair shops. That means smelters don’t need to fly in parts or labor. Everything’s already there.

Fast-moving technology and short lifespans

China didn’t just build fast. It also planned to rebuild fast. State-sponsored research centers like SAMI, GAMI, and NEUI helped Chinese producers move from 100,000-amp technology in the early 2000s to 660,000 amps by 2017. That’s faster than the West, where Rio Tinto is just now deploying 600,000-amp AP60 tech.

The result? Chinese smelters are often designed with 10–15 year life cycles and short depreciation schedules, not the traditional 30-year Western model. Smelters are built to be replaced, not preserved.

Lean assets, outsourced inputs

Western smelters often come with anode plants and full casthouses to make billets, rods, and foundry products. Chinese smelters skip that. Tianshan and others buy anodes from companies like Sunstone and only cast into ingot. Most of their aluminum is delivered molten to neighboring producers who make the value-added goods.

Accounting sleight of hand

There’s one last trick that helps keep capital costs low. In the West, smelter commissioning cost are capitalized — meaning they count toward total project cost. In China, those costs are booked as operating expenses. That alone can shave $200 to $300 per ton off the official capex.