Carbon Neutral Initiatives

February 4, 2026

China's aluminum production cap meets a changing global supply map

Written by Greg Wittbecker

The International Aluminium Institute (IAI) estimates that China’s primary aluminum production in 2025 totaled 44.2 million metric tons.

Other sources believe China has already exceeded its long-announced 45-million-ton production cap.

Since the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) announced the cap in 2017, the market has debated whether it would prove durable.

At the time, China was producing just 35.9 million tons of primary aluminum according to the same IAI estimates, leaving substantial “headroom” before the cap became binding.

For years, the assumption was that enforcement could be deferred. Nine years later, China has effectively reached the limit.

The question now is whether Beijing intends to enforce it.

Why China Should Adhere to Its Production Cap

China has historically taken a pragmatic approach to industrial policy, and aluminum production limits will test that discipline.

We believe the cap is likely to hold for several reasons:

Shift from primary to secondary aluminum

China is increasingly shifting aluminum supply from primary production to secondary sources. Many of the same companies that built China’s primary aluminum industry are now investing heavily in secondary aluminum capacity.

Secondary aluminum production requires approximately 5% of the energy needed to produce primary metal, aligning with China’s push toward lower-carbon materials. As China seeks to maintain exports of semi-fabricated and fabricated aluminum products, the ability to claim lower-carbon inputs has become increasingly important. Secondary aluminum helps meet that objective.

Access to low-cost Russian primary metal

China also has access to a ready supply of relatively low-cost primary aluminum from Russia.

The war in Ukraine and subsequent sanctions on Russian aluminum in many Western markets have redirected Russian exports toward China. While official third-party data remain limited, industry participants estimate that Russia is selling more than 2 million tons per year of Siberian aluminum into China, often at discounted prices.

Even if the war were to end, Russia is likely to face persistent distrust in Europe and the United States, limiting its ability restore traditional trade flows. China could remain a core export destination for years.

A 1% increase in China’s annual primary aluminum demand equates to roughly 460,000 metric tons of consumption. In 2025, Russia produced slightly more than 4 million tons and consumed just over 800,000 tons domestically, according to CRU Market Outlook data published in January 2026, leaving an exportable surplus of roughly 3.2 million tons. That surplus alone could support incremental Chinese demand growth for several years, allowing China to substitute Russian metal for domestic primary production.

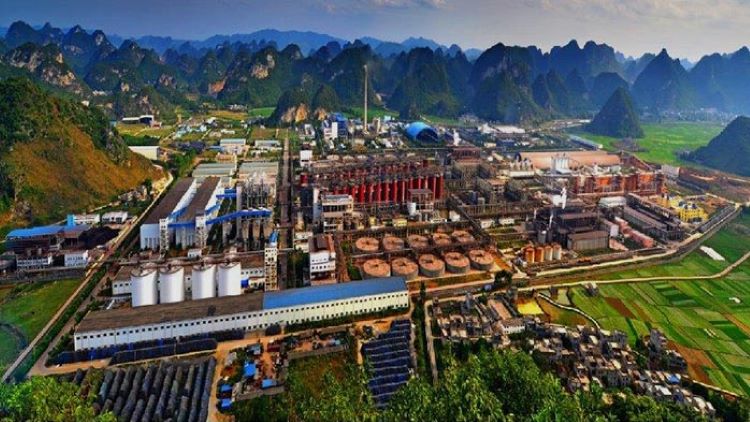

Overseas expansion, led by Indonesia

Indonesia is emerging as the primary center of global primary aluminum capacity growth outside China, reinforcing the view that domestic Chinese expansion has peaked.

The same Chinese firms that built much of China’s domestic primary capacity are now investing heavily in Indonesia. In effect, Indonesia has become a proxy for China’s next phase of primary aluminum investment. This mirrors Japan’s investment strategy following the oil shocks of the 1970s, when Japanese producers increasingly shifted energy-intensive aluminum production overseas.

CRU estimates that Indonesia alone will add just under 3 million metric tons of primary aluminum production between 2025 and 2030, compared with projected Chinese primary aluminum consumption growth of less than 2 million tons over the same period.

That comparison highlights how incremental supply growth outside China – even from a single market – could be sufficient to meet China’s demand growth, reinforcing the view that future primary aluminum expansion will increasingly occur outside China rather than domestically.

Acceleration of operating rights transfers

China’s system for transferring operating rights is also likely to gain momentum now that the production cap has been reached.

In 2017, the NDRC halted illegal capacity and stopped unauthorized project construction. At the same time, it effectively froze the issuance of new operating rights and introduced a system allowing existing operating rights to be sold, provided the seller permanently shut down capacity after the transfer.

This framework created a functioning market for operating rights and drove substantial capacity closures in legacy producing regions, including Henan, Shandong and Shanxi. Millions of tons of capacity were shifted from traditional production centers to newer, more efficient facilities in Yunnan, Inner Mongolia, Sichuan and Guizhou.

Now that the production cap has been reached, transfers are likely to accelerate, particularly in provinces with large legacy capacity bases. Shandong, Henan, Shanxi and Shaanxi are likely to be the primary sources of operating rights.

Given current margins in China’s primary aluminum sector, bids approaching $1,000 per ton of operating capacity would not be unreasonable.

Export constraints reinforce discipline

Export constraints will also require greater production discipline to avoid surplus buildup.

From 2000 to 2020, Chinese primary aluminum expansion was poorly aligned with domestic demand growth, leading to persistent surpluses that were exported in the form of semi-fabricated products. Beijing actively encouraged this behavior through a 13% export rebate program.

That rebate program ended in December 2024 as trade barriers increasingly blocked Chinese exports and rebates were seen as incentivizing excess fabrication capacity. The removal of export rebates represents a meaningful brake on surplus creation and reinforces the need for tighter production discipline.

Why it matters

Sustained discipline in China’s primary aluminum production would have significant implications for London Metal Exchange (LME) prices.

For the past two decades, LME prices have largely been anchored by the pace of new Chinese supply additions. That era appears to be ending.

The success or failure of China’s production discipline will play a central role in determining how far LME prices can advance in 2026 and beyond, as the market searches for a price level capable of incentivizing new supply growth outside China.