Decarbonization

January 20, 2026

LME high grade aluminum: How high is high in a post-China cost curve?

Written by Greg Wittbecker

The London Metal Exchange (LME) cash settlement has recently traded to $3,220 per metric ton ($/t), and forecasts from some analysts predict prices reaching $4,000/t, with 2026 averaging well into the $3000s.

What’s driving this meteoric rise, and is it sustainable?

In the short-term, the market is riding the wave pushing copper to fresh historical highs, with aluminum being carried along by broader bullish sentiment. In the medium and long term, the market is undergoing a structural transition.

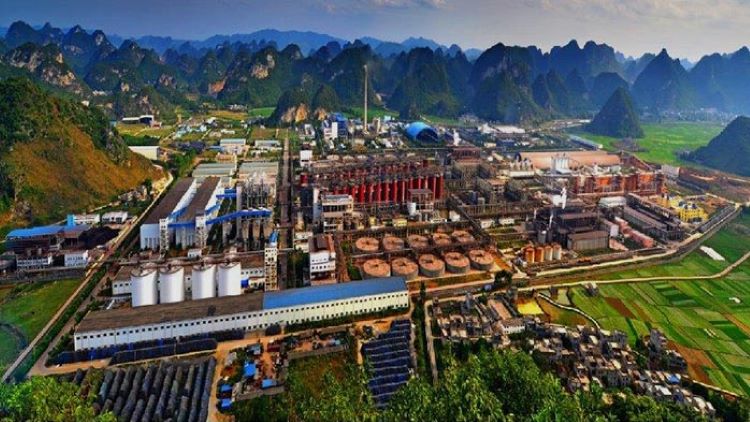

For more than 20 years, the LME cash price has been driven by Chinese fundamentals that have not been kind to aluminum. China relentlessly added capacity, quickly and cheaply. Capital costs in China were $1,000-$1,500/t of installed capacity. The LME was efficient in pricing aluminum at China’s clearing cost of incremental capacity.

Structural change in China is making all the difference

Things in China have changed dramatically thanks to two watershed events:

- National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) cracked down on illegally built capacity in 2016 and 2017.

Rogue production was shut down, and the NDRC imposed a licensing system for operating rights. This was analogous to trying to open a bar in your hometown: You can either ask the local government to grant you new operating rights, or you purchase existing rights from an operating bar owner.

Obtaining new operating rights from the NDRC became very difficult due to widespread abuse through illegally constructed capacity and a policy desire to allow demand to catch up with installed capacity.

This incentivized prospective smelter operators to seek out older, less efficient operators willing to exit the market. Operating rights began changing hands at upward of $1,500/t of capacity. This system gained further traction because of the second major change that occurred in 2017.

- The NDRC imposed a 45 million metric ton production cap on primary aluminum.

At the end of 2017, annualized production was 36.3 million tons, meaning the cap sat roughly 24% above prevailing run rates. At the time, the marketplace felt this cap allowed sufficient head room for the industry to continue to grow. There was also a skepticism that the NDRC would enforce the cap, and that local provincial governments would continue to ignore Beijing’s mandate.

The reality was the NDRC did enforce the operating-rights licensing system and did not ignore illegal attempts to add capacity.

Fast forward to 2026—nine years after the creation of the cap—and China has not exceeded the 45-million-ton limit. The market appears resigned to accepting it as law.

Why, you ask? One word: Indonesia.

As we wrote previously, Indonesia is the hot spot for new primary aluminum production. Some estimates foresee up to 13 million tons of new capacity over the next decade. This capacity is being built by the same Chinese companies that built inside China, using Indonesia as a proxy for their inability to expand domestically.

Indonesia capital expenditure will be higher than China

These companies will bring their expertise in building large capital projects to Indonesia, including technology, imported capital equipment, and some labor. However, they will not be able to fully replicate China’s domestic capital cost structure for several reasons:

- Significant capital expenditure (CAPEX) will be required for infrastructure such as ports, roads, power generation, and transmission grids. Chinese firms are adept at building infrastructure, as demonstrated by the One Belt One Road initiative launched in 2013, but it still comes at a cost.

- They will build it, but not as cheaply as in China, because supporting cluster industries (cement, steel, electrical equipment) do not exist locally in Indonesia. Much of this will need to be imported from China at a higher cost.

- Permitting may be as easier.

- Labor efficiency will not be as high.

Why Indonesia changes the cost curve

Bottom line: Chinese-owned capacity in Indonesia will be more expensive, perhaps $2,500/t of installed capacity or higher.

This higher CAPEX and replacement cost for primary capacity must be reflected in a higher LME clearing price to make these investments pencil out for Chinese producers. At the same time, projects outside China continue to advance. Finland, India, and Saudi Arabia come to mind. For these projects to be financially viable, they will require higher LME incentive prices extending into future years.

Beyond higher direct CAPEX, the prospect of significantly higher power costs also looms as a cost-push inflationary force on LME prices.

The pressure to build new data centers is not confined to the US.

While the US may be the largest consumer of data services, there is nothing inherently magical about locating data centers near demand. Fiber optic cable allows data to move from regions where power is more readily available to companies like Meta, Google and Amazon.

This means the global demand pull for power, already frustrating companies like Century Aluminum in the US, may present similar challenges to prospective smelter builders around the world.

To compete with data centers for power, aluminum producers will need higher LME prices to amortize higher electricity costs.

Why this matters

Current high LME cash prices may not be an anomaly. Cost-push inflation may require the LME to move higher—and stay higher—for longer in order to incentivize investment in primary capacity outside China.

The era of cheap Chinese primary aluminum capacity is dead and buried. It is time for the market to determine an incentive price that finally brings the rest of the world back into the business of producing its own primary aluminum.